Application of Developmental Kinesiology in EAT

This chapter delves into motor and postural development from early childhood and its connection to Equine-Assisted Therapy (EAT). It focuses on developmental kinesiology principles and how they guide therapeutic positioning on horseback for children and adults with movement challenges. The chapter explains how equine movement stimulates motor functions and supports therapists in improving gross and fine motor skills.

Motor and Postural Development in Early Childhood and the Role of Equine Assisted Therapy

In the Czech Republic, physiotherapy approaches are primarily grounded in developmental kinesiology and postural ontogenesis. These principles are vital when positioning clients during Equine Assisted Therapy (EAT) sessions and making therapeutic adjustments. This chapter will outline how these approaches are applied in EAT for physical, occupational, and speech therapists working with children from the age of three to adults, particularly those with neurological challenges.

EAT can be applied to infants and toddlers; however, treating this group requires specialised knowledge and skills from a therapist, which will be introduced in the fourth module of the course.

The Importance of Developmental Kinesiology in EAT

A sound understanding of developmental kinesiology is essential for therapists practising EAT, as it forms the foundation for working with children and adults. The physiotherapist evaluates the client to assess the quality and quantity of gross motor skills and then selects the therapeutic position on the equine's back to improve skill with less-than-ideal quality or to develop a new one. The progression of specific skills must follow the developmental scale, ensuring that therapists build the client’s abilities in a steady and structured manner. This creates a solid foundation for acquiring more complex skills that require greater balance and coordination. Without this knowledge, important milestones could be skipped, resulting in skills that lack stability and consistency.

These principles also apply to any age group, as injuries or accidents always affect movement patterns. Rebuilding from a steady foundation is essential to re-educating and regaining good-quality movement skills.

Human Motor Development: Genetic Programming and Environmental Interaction

Human motor development is a lifelong process influenced by genetically pre-programmed movement patterns and environmental interaction. Physiotherapists practising EAT must recognise the importance of movement quality at each developmental stage—such as rolling, crawling, sitting, and walking—and understand how to facilitate this process through EAT.

- Genetic Pre-programming: Basic motor patterns are hard-wired into the nervous system and emerge as the CNS and sensory systems mature rather than being learned through practice.

- Postural control, Gross and Fine Motor Skills: Skills such as head or trunk control, crawling and walking (gross motor) and grasping or manipulating objects (fine motor) are essential life abilities that can be developed through therapeutic positioning on a moving horseback. Developmental kinesiology provides a framework for understanding how these skills evolve and can be effectively supported in EAT.

- Biomechanical and Neurophysiological Factors: Motor skills improve as the CNS matures through processes like myelination and synaptogenesis. These principles apply equally to adults, especially those recovering from neurological conditions, where motor reorganisation is essential.

Assessing Motor Development in EAT

Therapists assess the quality and quantity of spontaneous and voluntary movements as key indicators of motor development. In EAT, these assessments are critical for creating treatment plans utilising the horse's movement to address specific motor challenges.

Maturation of the CNS and Movement Control

A clear understanding of CNS maturation is essential for therapists working with clients in EAT, particularly those with neurological challenges. CNS development impacts postural control and gross and fine motor and speech skills in children and is also relevant when treating adults recovering from neurological disorders.

- Myelination and Synaptogenesis: These processes enable more efficient neural communication, essential for motor control. As children’s CNS matures, they gain better control over movements such as walking. For adults with CNS damage (e.g., stroke or TBI), interventions may be needed to re-establish these pathways.

- Sensory Integration: The CNS relies on sensory inputs from the vestibular, proprioceptive, and visual systems to guide posture and movement. In EAT, the equine’s rhythmic movement provides sensory stimulation, helping children and adults integrate these inputs to improve balance, coordination, and motor function.

Motor Development in Early Childhood

The CNS still develops in early childhood, impacting gross and fine motor functions. Reflexive movements initially dominate, but as the CNS matures, control over movement becomes more voluntary and coordinated.

- Spinal Reflexes: Reflexes such as rooting, grasping, and the Moro reflex are vital for survival but are automatic and involuntary. These reflexes occur at the spinal level, with minimal input from higher brain centres.

- Caudocranial Myelination: Myelination progresses from the lower parts of the CNS (spinal cord) to higher brain regions (brainstem, cerebellum, and cortex). This development allows for more advanced motor control, starting with gross motor skills and evolving into fine motor skills as the CNS matures.

- Involvement of Higher Brain Centres: As myelination continues, control over movement shifts from spinal reflexes to more complex voluntary actions facilitated by higher brain centres like the cerebellum and cerebral cortex.

Therapeutic Application in EAT

Understanding the gradual maturation of the CNS helps therapists determine how to position and support clients on the horse during EAT. The horse’s movement provides a multisensory environment that promotes motor development, especially in children with emerging motor skills.

- Early Childhood (0-2 years): For very young children, EAT can help improve postural stability and head control through rhythmic movement, stimulating the vestibular and proprioceptive systems.

- Preschool Age (2-5 years): Children develop more control over their trunk and limbs as the CNS matures. More dynamic riding activities can challenge balance, coordination, and postural control while stimulating fine motor development.

- School Age (5-6 years): By this age, children’s CNS has developed sufficiently to allow for greater independence in movement. EAT sessions can focus on refining gross and fine motor skills, using the horse’s movement to support complex therapeutic activities.

Clinical Implications

Delayed or abnormal myelination can result in motor development disorders. For example, in cerebral palsy, brain damage disrupts the typical progression of motor control, leading to impairments in movement, coordination, and muscle tone. EAT offers a therapeutic environment that can facilitate neural reorganisation and improve motor function for such individuals.

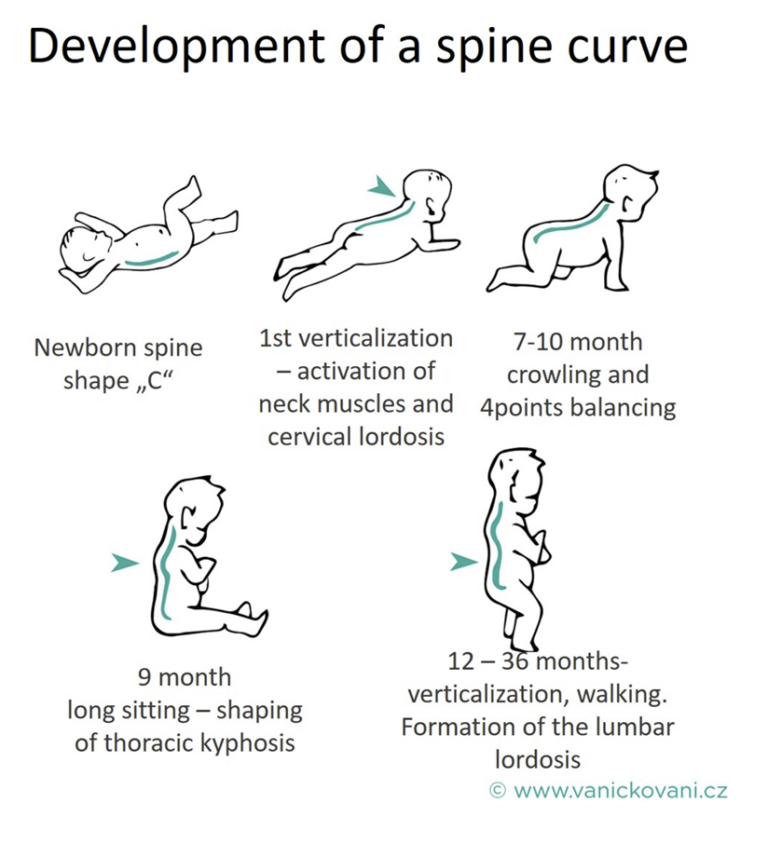

Principles of Posture Development: A Foundation for Motor Control

Posture development is fundamental to all motor functions, and therapists must understand its principles when practising EAT. At birth, postural immaturity is evident due to the underdeveloped CNS, but postural control becomes increasingly refined as the child grows.

Posture development is a fundamental aspect of motor growth and is closely linked to the maturation of the CNS. In the early stages of life, the CNS is immature, affecting gross and fine motor control. Posture gradually becomes more organised and refined as the CNS matures, influenced by sensory input and motor practice. Understanding the principles of posture development is crucial for therapists, particularly in Equine Assisted Therapy (EAT), where posture is often a central therapeutic focus.

Dependence on Sensory Inputs for Postural Development

The development of posture is highly dependent on the integration of sensory inputs, particularly from the vestibular, proprioceptive, and visual systems. These sensory systems provide critical information about the body’s position in space, which the CNS uses to coordinate and maintain postural stability.

- Vestibular System: This system, located in the inner ear, is responsible for detecting changes in head position and movement. It plays a crucial role in maintaining balance and coordinating postural responses to changes in body position.

- Proprioceptive System: Proprioception involves the body’s awareness of its position and movement in space. Receptors in muscles, joints, and tendons provide feedback to the CNS about the position of the limbs and trunk, helping to adjust posture as needed.

- Visual System: Vision provides important feedback about the body’s orientation relative to the environment, especially when coordinating postural adjustments in tasks that require balance and locomotion.

In EAT, the equine’s rhythmic movement provides continuous sensory input, challenging the client to adjust their posture in response to the horse’s gait. This dynamic environment is particularly beneficial for individuals who may struggle with integrating sensory inputs, as it encourages the development of postural responses through repeated, real-time adjustments.

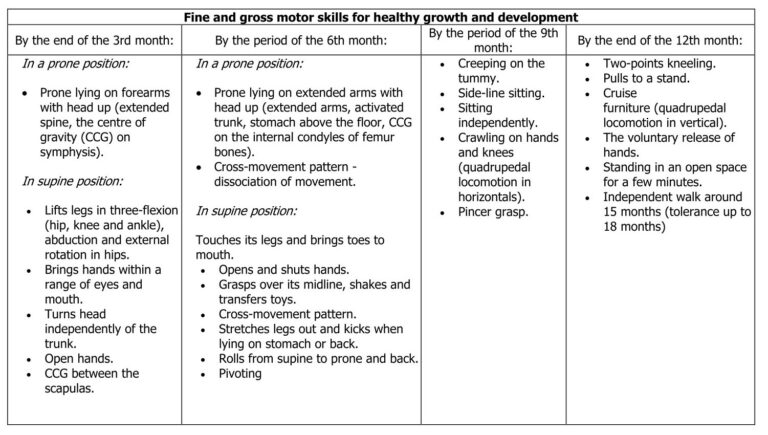

Key Stages of Postural Development (see the detailed table below)

- Head Control (0-3 months): Early head control lays the groundwork for further postural stability, particularly as children learn to maintain their head against gravity.

For EAT: If the client skills correspond to this stage, therapists should focus on providing gentle, stable positions on horseback, where client can experience equine movement while developing head control in a safe and supportive environment. - Trunk Control (3-6 months): Infants develop greater trunk strength, which allows them to roll. In EAT, positioning clients to promote trunk stability is essential for neurological and motor rehabilitation.

For EAT: If the client skills correspond to this stage, the horse’s rhythmic movement can encourage trunk stability and support the development of reaching and grasping. Therapists might consider positioning the child to allow them to engage their arms and hands while maintaining a safe, supported posture on the horse. - Sitting and Balance (6-9 months): Independent sitting reflects significant progress in postural control. For therapists, using the equine’s movement to challenge and strengthen these postural muscles in children or adults can be highly beneficial.

For EAT: If the client skills correspond to this stage, positioning on a moving horse provides an excellent opportunity to challenge and strengthen the child’s postural muscles. The equine's rhythmic motion helps facilitate balance reactions, trunk control, and coordination. Therapists can adjust the horse’s pace and movement to give each individual the right amount of challenge. - Standing and Crusing (9-12 months): Standing and walking mark the transition to more complex motor tasks. In EAT, the equine’s movement can help reinforce these gross motor mileston

For EAT: If the client skills correspond to this stage, it allows therapists to focus on increasing the complexity of postural control and balance activities during EAT sessions. Therapists can use different therapeutic positions and dynamic movement patterns to encourage the child to engage their core and leg muscles, promoting stability for standing and walking. - Independent Walking and Exploration and Fine Motor Skills (12-15 months): By 15 months, most infants have mastered the skill of independent walking. Their steps may be wobbly initially, but their gait becomes smoother and more coordinated as they gain confidence.

For EAT: At this stage, therapeutic positions can be further varied to support the development of balance and coordination needed for walking and fine motor skills. Clients can be encouraged to reach for objects or engage in playful activities while on the horse, enhancing their gross and fine motor development.

Positioning the client on horseback in various ways can enhance these developmental processes by providing appropriate challenges that promote motor growth. Moreover, the sensory input from the equine’s movement can help regulate the proprioceptive and vestibular systems, which are integral to motor development.

Postural control in both children and adults is influenced by biomechanical and neurophysiological processes. In EAT, the movement of the equine provides a dynamic platform for enhancing postural stability, balance, and coordination in clients, making it an effective therapeutic tool.

- 18 months – period of locomotion obsession – there is not perfect coordination between upper and lower limbs, runs, stops, turns, does not avoid obstacles, stable, rarely falls, climbs onto the couch, manages two steps backward, sits on a stool by themselves, squats, climbs stairs with support, throws and kicks a ball.

- 19–21 months – walks up and down stairs, alternates feet going up.

- 24 months – walks on tiptoes, jumps off a small height, cannot jump yet, runs well, puts hands in front when falling.

- 2.5 years – goes up stairs without holding on, jumps with both feet, stability.

- 3 years – runs perfectly, stands on one leg, jumps both forward and upward (5 cm), alternates feet going up and down stairs, controls a tricycle, has achieved upright posture and coordination of limbs.

- 4 years – stands on one leg for a few seconds, jumps forward with a run-up.

- 5 years – hops on one foot, does a forward roll, catches a ball.

- 6 years – can stand on one leg with eyes closed, throws objects skillfully, confidently kicks a ball, jumps off steps.

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessPT 1 Therapeutic Impact of EAT

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessPT 2 Application of Developmental Kinesiology in EAT

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessPT 3 EAT Techniques I - Choosing an Equine

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessPT 4 EAT techniques II - Using the Equine's Movement Potential

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessPT 5 EAT techniques III - Choosing the therapy position

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessPT 6 EAT techniques IV - Correction of the therapy positions and use of equiment

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessPT 7 Practical examples of using the techniques

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessPT 8 Case Reports

You do not have access to this member section

Get access