Sensory Processing - part I

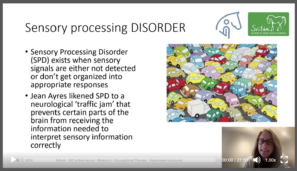

This chapter examines sensory processing, focusing on its significance as the foundation for skill development in EAOT. Sensory processing involves the integration of eight senses—sight, smell, taste, hearing, touch, vestibular, proprioceptive, and interoceptive—that together influence how we experience and interact with the world. In EAOT, the equine environment provides rich sensory input to help regulate arousal levels and support clients with sensory processing difficulties. This chapter also explores how specific sensory systems like proprioceptive, vestibular, and tactile input play essential roles in skill development, emotional regulation, and functional independence. Through EAOT, therapists can utilise multi-sensory strategies to help clients reach optimal alertness and readiness to engage.

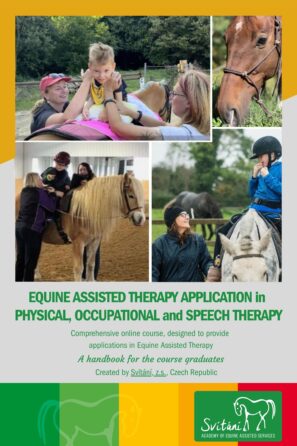

Welcome back to the occupational therapy module in the Equine Assisted Therapy course for Physical, Speech and Occupational Therapists. This is chapter three, and it is Sensory Processing as a Foundation for Skill Development. Let's have a look at sensory processing.

I think we all know a little bit about it, but sometimes, it's good to take a step back and review what we know instinctively. Sensory processing is linked to how we are in the world, our emotional state, our alertness, and the very complexities of our being, yet we take it a little for granted. And yet, as you're all on this course, somehow, you haven't acknowledged the power of the echoing environment to make us feel better.

Let's recap the sensory systems. This slide shows the sensory systems, which is where we start with sensory processing. As you know, we have eight senses.

We have the five, which are the commonly recognised ones, which is sight, smell, taste, hearing, and touch. And then there's the two really key ones, vestibular and proprioceptive senses. And then there's the interception, which has growing recognition over the last number of years.

And, you know, it is an important one and one that can be dealt with in the equine environment. Goodness gracious, I have lots of children who come with constipation, and, you know, it's the one thing that their parents rely on to support that movement within the body. And, you know, and it can help during toilet training.

I have a little girl who is six, and she's going through, she has global developmental delay in autism, and she's going through toilet training at the moment. On the days she comes to her sessions, she has had much more success because she has a better awareness of what's going on in her interceptive system.

Tactile, the tactile system, you know, we need just to acknowledge what it's for. It's for light touch and deep pressure, and it acknowledges temperature, hot and cold.

Vision. How many children spend a lot of time watching highly visual images on iPads and how dysregulating can this be?

Olfactory. A smell can resurface old memories and associations.

Gustatory. Do we like spicy food, plain food? Do we like to chew things? I'm a definite toffee eater. If I were stressed, I would choose a toffee. Chew, get some input in through my jaw.

Interception, knowing that we need to go to the toilet, that we're hungry or that we're thirsty. And also, that feeling of overwhelm when we don't quite know what's going wrong. But then remember that we've not eaten for hours. I'm sure that's happened to most of us.

Here we are with all of our different sensory systems, all receiving masses of information during the day. And I suppose it's just really important to acknowledge at this point that our level of arousal or alertness changes right throughout the day. When we wake up in the morning and its cosy in the bed and, you know, it's cold outside and it's raining and it's dark, we're still in a drowsy sleep state. But we know that we have to get up into a calm, alert stage state to get to work. We take opportunities to drink coffee or turn on the lights, turn on the radio, stimulate those different senses in order to get us to a calm alert state of arousal that we can go to work. And then that'll drop off.

You know, we'll work hard for a little while, and you'll see where the graph goes up above the calm alert, and then it drops into hyper-arousal. That could be the just early afternoon, just after lunch slump where it's actually kind of hard to get going again. And then we'll go into an important meeting, and we might go into hyper-arousal and high alert. And, you know, you're trying to work your very best, and things are not going great. You'll go up into high alert, and then you might go to the gym, or you might go and meet friends after work and all of that. Your alertness is constantly changing, and we support that those changes within our bodies in a very natural and instinctive way without even having to think about it.

Let's have a little look at some of those sensory systems and, why are they ultimately important and how is it that the equine environment is incredibly potent at supporting regulation in these different senses?

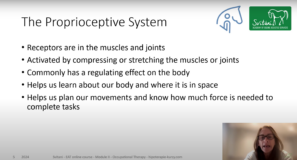

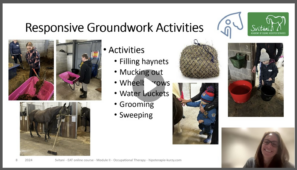

Let's have a look at the proprioceptive system. This is the master sense. It is the one that will bring us up before low arousal, the one that brings us down if we're over aroused, the one that regulates or balances. It brings us into the calm, alert state for the task at hand. It is the one that will support anxiety. It's the one that supports gross motor and fine motor development. It's even the one that helps us to know where our tongue is in our mouth and supports speech production. This is available in bucket loads in the equine environment. In groundwork, have a think about groundwork where you can do pushing, lifting, scooping, grooming, pouring water, lifting the muck heap, mucking out, carrying saddles, mounted activities through the response of the body to the movement of the horse, reaching games, throwing games, trotting, lying on a horse, turning on the horse to change position.

The list is endless. In a clinical environment, we are limited to tug-of-war games, going on a scooter board, etc. The beauty of the equine environment is that the child can be passive in the process of getting and receiving all of this proprioceptive input.

They can sit on the horse and allow the rhythm and movement to provide the input. This is the perfect way to increase motivation. The child or the adult gets that feel-good feeling, and then they want more.

Proprioceptive is input from our muscles and our joints, helping us to understand where our bodies are in space and allowing us to move and control. Sitting on a moving horse requires the client to activate core muscles and adjust their posture, which provides proprioceptive input throughout the body. Activities like grooming the horse, carrying saddles or leading provide additional proprioceptive input through resistance, which can help with body awareness, emotional regulation and coordination.

For children with sensory processing difficulties, proprioceptive input is often very calming and regulating. In EAOT, brushing the horse's coat with different levels of pressure or leading the horse over different terrains allows the client to engage in proprioceptive activities that can help to regulate the nervous system. Let's just take a moment to look at these pictures.

We have the first picture is where is the proprioception happening and we've got three children hanging from monkey bars and you know, children in their development once they get past the toddler stage this is what they want to do. They want to go to the playground, they want to climb, they want to hang, and all of these things are flooding their bodies with the input that they need. And unfortunately, when there's a problem with sensory processing the children or perhaps with physical functioning children cannot actually go and get that input that they need by themselves. They need support. But in the first picture, we have three children hanging. Each of them is clenching their muscles on many levels in order to hold the weight of the girl on the bottom. There are oodles of proprioceptive inputs going to their brains.

In the other picture, we have a little girl who's standing on a horse and not that I would advocate standing on horses, but what it is to illustrate the fact that she's on a moving, unstable platform and she is standing, and she's holding her balance she's having to work really, really hard to do that. The same effect can be gotten in sitting. Next, we're going to have a look at the vestibular system, and the vestibular receptors are based in our ears. There's the three semicircular canals, and they acknowledge and detect rotational movement, which is always a little bit disorienting and always alerting.

The otoliths then they detect linear and velocity linear is straight lines straight line movement and velocity is the speed. Vestibular input is really important for balance and spatial orientation, and it works with the visual and proprioceptive senses together. It helps us to understand where our head is in space. It coordinates the eyes, the head, and the body and helps modulate muscle tone of all things. Vestibular input is always stimulating and lasts in the body for about eight hours, and the classic example of this might be when a child is in the playground and enjoying the spinning chair, and often they ask for help, and a well-meaning adult spins them fast, and they giggle, and you may forget, they may forget to settle the system by rotating equally in both directions. The child seems fine but later that night at bedtime is agitated and may even vomit, and this is a throwback to overstimulation of the vestibular system earlier in the day.

However, vestibular input combined with proprioceptive input is alerting but also organising. For example, jumping on a trampoline, you clench your muscles to create the upward impulsion and then gravity pushes you back down and; in order to hold your balance, you have to clench your muscles again but added to that, your whole body weight hits the trampoline bed, and you get a jolt of input right up through the spine and all of the joints in the hips the knees the ankles it's a massive dose it's very organising even though it is vestibular.

Let's test our vestibular system. I challenge you to put a piece of string on the ground about two metres like a good length of string on the ground, do about five or six spins fast in one direction, and then open your eyes and walk along that line. Try and stay steady on the line, and you will have upset your vestibular system, and that will prove much more difficult than usual. The vestibular system is the sense of balance and movement, and it's fundamental for postural control and coordination. That's why you had difficulty walking along that piece of string. The horse's movement provides continuous vestibular stimulation through the three-dimensional movement of its gait. This can be beneficial for children who are either seeking vestibular input, those who crave intense movement, or those who are sensitive and need graded exposure to vestibular input.

The horse's movement can be adapted to meet the client's needs. We can change pace, we can change gait, we can change direction, or, you know, we can alter the intensity of the vestibular input at any point. For a child with low muscle tone, we might use a slower rhythmic gait to stimulate the vestibular system gently. For a child with high arousal who benefits from stronger movement, we might use a faster or more variable gait.

What many people don't know is that the vestibular system is responsible for eye muscle control and tracking and also for regulating muscle tone and for self-regulation, including focus attention and impulse control, distractibility, arousal levels and organisational skills. Now, that's a really big remit and a system that can easily be targeted in the equine environment. We've had a look at the two huge systems, and we're going to have a quick look at some of the others now.

The tactile system. The tactile system is the foundation of sensory processing and begins through our tactile system. Coming through the birth canal is a massive, deep pressure and tactile experience, and tactile input impacts how we interact with our environment.

Horses offer different tactile experiences, from the softness of their coat to the firmness of their mane, from warm breath to the textures of hay or leather tack. Many of the children we work with will struggle with tactile defensiveness or tactile-seeking behaviours. Engaging with a horse, such as petting, grooming, or feeding, can provide that just right challenge to help them either tolerate or explore these tactile experiences.

For a child who's tactile defensive, we may begin by simply standing near the horse and observing, then slowly progress to stroking the horse's neck or mane, moving at the child's pace to ensure they feel comfortable and in control. What about auditory and olfactory input? The natural setting of the equine environment provides a host of auditory and olfactory experiences. Birds chirping, the sound of hooves, the smell of hay or leather.

These sensory inputs, although not always the primary focus, can significantly impact a client's arousal level and emotional regulation. For children with auditory sensitivities, gradually acclimatising them to these sounds can help them develop coping strategies and enhance their tolerance of novel or unpredictable sensory input. The power of the horse is that all of these sensory inputs happen simultaneously.

Unlike in a clinical setting where we might target one sensory system at a time, the horse provides a constant stream of vestibular, proprioceptive, tactile, auditory and even visual input. The client's nervous system processes these inputs in real time, and our role as therapists is to make sense of that information, support regulation, and encourage functional outcomes. One of the best ways to understand sensory processing in other people is to be more aware of how we manage our own sensory processing.

What are your sensory preferences? What is it that you like to do to become more alert? I know if I'm working hard, I will chew my pen, and that gives me proprioceptive input through the temporomandibular joint in the jaw, and that is more organising. I've said before I like toffee and that does the same thing. Some people like to get up and go for a run. Some people like exercise and movement, which will always provide vestibular, proprioceptive input, and that supports calm, alert states. Some people like caffeine or fizzy drinks. Some people like sweet things in order to help them change their regulation. Some people go for a massage to relax. Some people like fruity toothpaste, and some people like minty toothpaste, and that's all that input in the mouth that is very regulating and organised and changing from an under-aroused state to a just right state. What about those of us who get stressed and do the housework? Clean the house, all of that physical activity, two hands together, sweeping, hoovering, scrubbing, carrying buckets, all of those things are regulating and bringing us down from that over-aroused state back to a just right and you sit down and have a cup of tea and go. Some people like a rocking chair. Some people like to sleep. We all have different sensory preferences. I myself am an avoider. I would not go on a roller coaster if you paid me a million pounds. I hate vestibular input. I hate the arousal of it.

But then there are many of you out there who just would love to go on a roller coaster and when you come off it you go let's go again. There's two diametrically opposed sensory profiles and how I would choose to get myself alerted would be to have a cup of coffee. Much more avoiderish.

Just have a think about some people, walk and learn. Do you think about teenagers and how they like to walk and talk to describe their day to their parents? And then there's the aspect of how much, how often, and for how long you have to engage in these activities. Going for a swim. Can you get away with a 15-minute swim? Will that make you feel better? Or do you have to keep swimming for an hour? And the benefit of the horse in all of this is that it works very fast.

Rather than swimming, which is quite a dilute activity, it can take a child with regulation difficulties, maybe the hour to regulate in the pool, whereas you can achieve that in 15 minutes on the horse because the input is multi-sensory. It is regulating in an intense but easy to absorb way. I've been talking for a few minutes now, 15 minutes.

I'm sure you're all starting to feel a little bit; oh, this is hard work. What I'd like you to do is I would like you to note how you feel, and I'd like you to stand up and do 20 jumping jacks. Put me on pause and then come back, sit down and note the change in your posture, in your alertness, in your engagement and your readiness to learn.

And it is just a small exercise for you to experience in a very controlled way, the benefit of changing your engine. When we're learning about managing alertness, we talk about our engine, which is our internal drive. Sometimes, we need our engines at different speeds.

When we're going to sleep, we need to go into low gears, and we need to slow down our engine so that we can down-regulate to sleep. In school, we need to be calm and alert because you can't be jumping around the place or in a meeting as adults. A revved engine is where you want to be enjoying the party. You want to go, and you want to be a little bit jizzy. You want to be calm alert, but you want to be calm alert for a happy occasion where you're socialising, and you're moving around, and you're maybe passing out drinks or whatever it is. And then there's yellow, it can also be on the positive side when you're ready for an exciting thing, or it can be on the negative side where anxiety is building up, and you're anticipating something, and you're just feeling not quite right. And then there's red which is the engine is in overdrive. You have just lost it. What we need to do is think about how we change our own engines and noticing the signs of somebody's engine being in these different states that we can support them to move it into different states.

We all use sensory strategies to bring ourselves to the calm alert state needed for work or the revved engine to get lots done. We can drink herbal tea and turn off the lights or turn them down to regulate to sleep. You know this is why sleep routines are important for children with sensory processing difficulties to give them time to down regulate and to support them to change their engine into the right speed for sleep.

We were just looking at the alert programme, the engine speeds from the alert programme, and I just thought I'd show you this other option, which is the sensory ladders. And the first sensory ladders were made in 2001 for adults receiving help with mental health difficulties as part of the Be Smart programme in the UK. And it became recognised and promoted as best practise across the UK and Ireland and resources and teaching about the programme were shared across the two countries by Kath Smith who developed it.

And I suppose of notice that Kath was influenced by the alert programme that we were just talking about, and it offers therapists the top-down approach to looking at the development of a person's self-awareness and self-regulation skills in collaboration with others, including, you know, originally it was with ward staff in acute psychiatric inpatient units but completely expandable to other settings. Now an OT in the UK, Rona Harkness has developed a programme called Sensory Transitions in the equine setting, and she has incorporated the use of the sensory ladders for children with disabilities to become more aware of where the horse is at and also where they are at and over time to increase their awareness and ability to change regulation.

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessOT 1 Core OT Values

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessOT 2 Skill Development in Children and Adults

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessOT 3a - Sensory Processing - part I

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessOT 3b - Sensory Processing - part II

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessOT 4 Groundwork and the benefits

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessOT 5a Why the Equine Environment? - part I

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessOT 5b Why the Equine Environment? - part II

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessOT 6a Case study I - Cri du Chat

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessOT 6b - Case study II Autism Spectrum Disorder and Anxiety

You do not have access to this member section

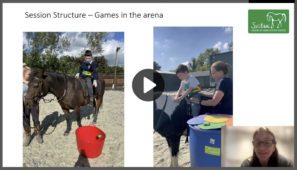

Get accessOT 7 EAOT Session Structure

You do not have access to this member section

Get accessOT 8 Occupational Therapy Application Quiz

You do not have access to this member section

Get access